Theatre as method

Dr Alice Cree & Lindsay Nicholson

01 May 2023

Photo by Pixabay

Learning Aims and Objectives

To introduce theatre as a method of inquiry in inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary research, and examine what it can offer us in terms of studying and responding to global challenges and societal injustices.

- Examine what theatre as method is and how it has been applied in a range of contexts.

- Explore theatre as a means of generating new knowledge.

- Critically examine how theatre as method and practice can open up new spaces of dialogue and ways of understanding contemporary global challenges.

- Advance understanding on the critical potential and value of theatre methods, as well as some of the complex ethical questions that might emerge.

Rehearsed reading of 'Women Warriors' (Workie Ticket Theatre CIC 2019). Copyright: Cree 2019.

Outline of Method

As an autonomous activity of performance, theatre can be traced as far back as 6th century BC Greece, although if more broadly understood we can see theatre emerge much earlier in the form of dance and ritual. The act of spectating (and later, 'spect-acting'; see Boal 1974) is at the heart of theatre; the word 'theatre' itself comes from the Greek 'theatron', meaning 'a place of seeing'.

Theatre as we understand it today is the product, practice, and process of dramatic performance, although the boundaries between these are not clear cut.

- As a product, it often (but not always) involves the performance of a real or imagined event, by actors, in front of a live audience.

The practice and process of theatre-making can involve activities including embodied story-telling, game-playing, improvisation, writing, directing, producing, acting, 'spect-acting', and many more.

There are strong links between theatre-making, activism, and social justice. Augusto Boal (1992) believed that theatre should be a force for social change: "Theatre is a form of knowledge; it should and can also be a means of transforming society. Theatre can help us build our future, rather than just waiting

What can theatre do?

Definition: Theatre methods in research involve the co-production of embodied and verbalised modes of story-telling, as a means of understanding cultural, political, social, and environmental issues.

Who Does Theatre?

The practice of theatre-making requires skill, experience, and training, and it matters how we position ourselves as researchers in relation to that creative process. Are we collaborators? Spectators? Analysts? Students?

Engaging with theatre-as-method in research will usually necessitate doing one of two things:

1) Working with trained theatre practitioners/writers. For most people interested in using theatre-as-method in their research, collaboration and co-production will be key.

or

2) Skills development. The skills that go along with theatre-making and practice can be learnt over time. For example, Cardboard Citizens offer training courses in Theatre of the Oppressed methodology, or you can experiment with improvisation at The Suggestibles School of Improv. Even a small amount of experience using theatre games can be useful for adding a twist to traditional qualitative methods such as focus groups.

Workshop for 'Women Warriors'(Workie Ticket Theatre CIC, 2019). Copyright: JoJo Kirtley 2019.

How can you use theatre?

'Theatre in research' can mean different things. Some of the ways we might incorporate theatre into our work might include:

Theatre as co-production and collaboration

Working with theatre practitioners to co-produce research and performance can generate exciting new creative insights, and take our research to unexpected places.

Theatre as method

Theatre can be used as a research method in its own right, and is a fantastic way to encourage research participation among hard-to-reach groups. Methodologically, theatre can give us a new perspective on participants' worlds and experiences, while offering the tools for them to articulate things through their bodies that are difficult to put into words.

Theatre as public engagement

Turning research into theatre is a brilliant way of engaging new audiences with your work! This could involve working with a script writer or theatre maker to translate interview and focus group material into a piece of theatre, which could be verbatim/documentary style, fictional, or anything in-between. Theatre can bring research to life, challenge people's perspectives, and open up new spaces of dialogue.

Theatre as object of inquiry

Theatre and performance can be rich sites of scholarly inquiry and analysis. Particular kinds of theatrical performance can offer important interventions on issues of human security, social justice and more, and an examination of these can help us understand such topics in new ways.

Theatre methods

Logos for the ‘Conflict Intimacy and Military Wives’ research project and Workie Ticket Theatre Company

Theatre in Action

Case study: 'Conflict, Intimacy, and Military Wives: A Lively Geopolitics' (Dr Alice Cree, Hannah West, in collaboration with Workie Ticket Theatre CIC. Funded by ESRC).

Project abstract: In a departure from masculinized narratives regarding the nature and sites of war, this research explores ‘conflict’ from the perspective of military wives, as something which plays out in intimate domestic spaces and personal relationships. It uses theatre techniques inspired by Augusto Boal and Bertolt Brecht to help us think differently about what the real lived impacts of conflict and deployment are for military families. The project, which has taken place online via Zoom due to the COVID-19 pandemic, explores how participatory theatre can not only empower military spouses, but also change how we approach ‘conflict’ in political geography.

Methods: Interviews, focus groups, group theatre-based workshops, participant observation.

Goal: To collaboratively create a piece of theatre, to be performed at Northern Stage (Newcastle Upon Tyne) in June 2022.

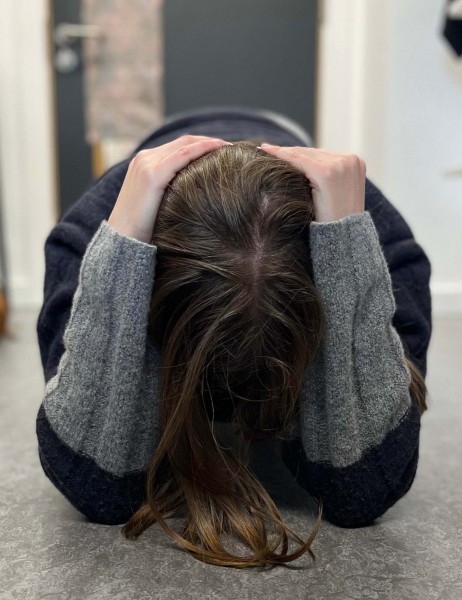

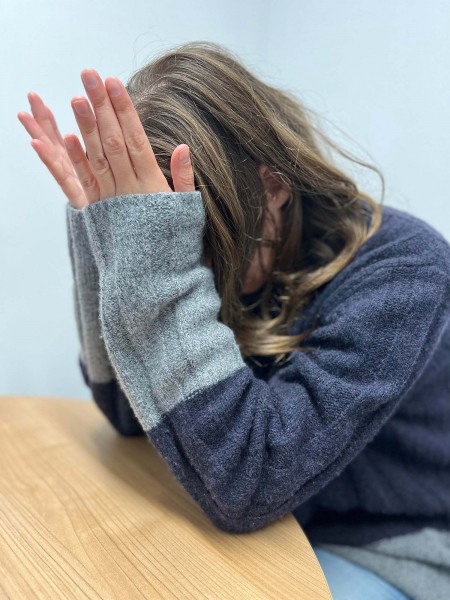

Snapshot 1: Image theatre

In a workshop on 'War', participants discussed how much they thought about the reality of their partners going away to war, what the scariest parts of it were, and how it impacted them at home. They then decided together on which ideas and feelings they wanted to visually represent, and created freeze-frames (still images) to convey these. These images became powerful visual representations of feelings that were quite difficult to articulate verbally, for example feelings of frustration and fear when 'comms' (communications) go down, and attempts to push the idea and reality of war away from them.

Note: An actor was used to recreate the images in the gallery below, created in the research workshops, in order to protect the anonymity of research participants. Activities designed and facilitated by Lindsay Nicholson (Workie Ticket Theatre CIC).

Snapshot 2: Biomechanics

An acting system which relies on motion rather than language or illusion

In one workshop, we asked participants to create the 'military machine'. This was a series of moving images that participants would all act out at the same time, which reflected their understanding of how the military functions. By silently using their bodies to 'perform' the military machine, participants were empowered as agents through which violent state power can be understood. We gained insight into how military spouses view the military as functioning through secrecy and the performance of masculinised discipline.

Note: An actor was used to recreate the images created in the research workshops, in order to protect the anonymity of research participants. Activities designed and facilitated by Lindsay Nicholson (Workie Ticket Theatre CIC).

'The Military Machine'

In this clip, we can see the participant silently zip her mouth shut, lock it with a key, then throw the key over her shoulder. She told us that this was to represent never knowing how much she could share with her partner about home life when he was deployed, in order to keep him safe. She also said it was about the inability of individuals in the armed forces to speak up for themselves at work. We viewed the action in a different way, understanding it to represent the secrecy of the military institution. Another participant said that secrecy was central to her idea of the 'military machine'.

The Military Machine 2

In this clip, the participant taps her watch repeatedly. She said that this reflected the emphasis in the military on discipline and timekeeping.

The Military Machine 3

In this clip, the participant does a smiley and happy face followed by an angry face, in quick succession. She told us that this was representative of how dichotomous the military is, and how so much of its functioning relies on a performance of being 'two-faced'. There is, she told us, the face that is presented to the public, and the face that exists behind closed doors. She said this also reflected how her husband behaves towards his superiors, versus what he says about them behind their backs.

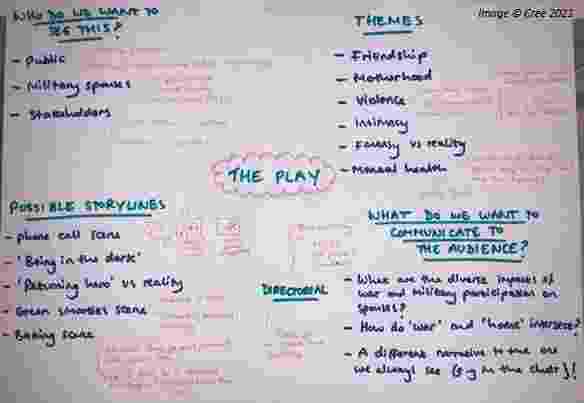

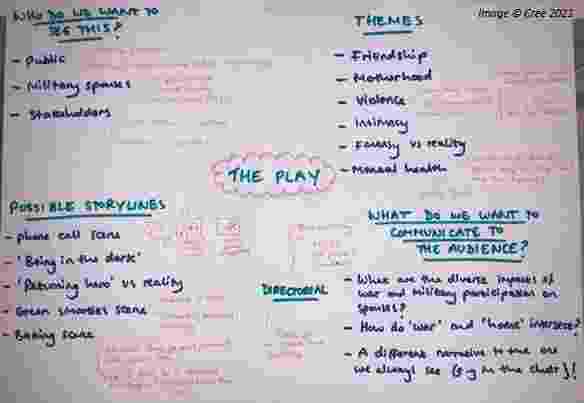

Spider diagram from the beginning of the writing process for the play. Copyright: Cree 2021.

Snapshot 3: Putting the research on stage

After analysing the interview and theatre workshop data, we have established a number of themes which we want to address in the final play. We have also collected a number of 'scene' ideas and topics from participants, which reflect the kinds of stories that we want to tell.

The first stage of the writing process has involved 'mapping' these themes and possible storylines, alongside important notes on who we want to see the play and what we want to communicate to the audience. We gradually began to build up a picture of key characters, their story arcs, as well as the broader style of the piece. We are now writing the play scene by scene, with substantial input from participants on character and storyline development.

What kind of research is it appropriate for, and who could be involved?

Theatre can be a powerful tool for social justice and change. It lends itself well to all kinds of participatory and community-driven research, particularly among hard-to-reach, marginalised, or disempowered groups. Research participants do not need to be trained in theatre, and the goal doesn't have to be to produce a play!

For Water Hub members, theatre-as-method could be useful for exploring the following kinds of issues:

- Gendered and racialised impacts of climate change

- Community-led approaches for tackling water insecurity

- Values of water among disempowered groups

Practicalities

- Training and costs of collaboration: If you are not skilled in making theatre yourself, you will need the resources (time, money) to involve collaborators. Theatre-makers must be paid appropriately for their time and acknowledged for their intellectual and creative contribution.

- Costs of production: If you are making a piece of theatre to be performed on a public stage, this can be costly. You will need to think about: writers; actors; directors; producers; stage managers; lighting; sound; hiring the performance space; set design; promotion of the play... the list goes on!

- Space: If you are using theatre-as-method with participants, where will you hold the workshops? How might this work in the context of international research? Pedagogically, face-to-face theatre is usually preferable due to the tactile and intimate nature of this type of creative collaboration. However, online platforms can work too provided you think about: access to technology; ensuring the safety of your participants when you are not in the room together; anonymity; how online platforms store any recordings you make, etc.

Ethical Considerations

There are a number of ethical questions which you will need to carefully consider when preparing to use theatre-as-method in your research...

- How will you protect the anonymity of your participants? This is potentially difficult when you are using performance-based methods.

- How will you ensure informed consent for different levels of participation?

- How will you tell your participants' stories? Will you fictionalise them, and what will the implications of that be?

- What will an ethical 'staging' of your research look like? Who decides? Who has final approval?

- What measures will be in place to safeguard collaborators?

- How will you prevent participants from being 're-traumatised'? Consider how you use performance-based research methods, and how participants will see their stories performed on stage.

- What level of involvement will your arts collaborators have? How will you ensure they are appropriately credited and paid for their work?

Summary

- Theatre methods in research involve the co-production of embodied and verbalised modes of story-telling.

- Theatre can be used in interdisciplinary research in a number of different ways, including: as collaboration and coproduction; as method; as public engagement; as object of inquiry.

- It will usually involve collaborating with arts partners, but you can also pick up useful theatre skills by taking part in specialist training.

- There are countless ways that you can engage theatre methods, particularly in participatory research. Even theatre games can be useful for beginning to talk about, for example, power relations and structures of oppression.

- Theatre can be a powerful tool for social justice and change. It lends itself well to all kinds of participatory and community-driven research, particularly among hard-to-reach, marginalised, or disempowered groups.

- Practical considerations for using theatre in research include training and collaboration costs, the costs of production, and finding the appropriate space to do the research.

- You will need to think about how you keep your participants safe, how you will protect their anonymity, and if/ how you will put people's stories on stage.

If you are interested in exploring how theatre-as-method could enhance your research, please feel free to contact Alice to talk through your ideas: alice.cree@newcastle.ac.uk