Citizen science for bottom up management of shallow groundwater

26 May 2022

This piece has been updated since it first appeared to incorporate Dr Alemseged Tamiru Haile's thoughts and responses to World Environment Day 2022.

Citizens are beneficiaries of environmental services, but they can also cause harm to the environment. Balancing the benefits from the environment and its conservation cannot be achieved without a meaningful participation of the community. Citizens continuously interact with their environment and as a result acquire local, indigenous knowledge, most of which has been passed from generation to generation. Their engagement in citizen science helps them to further understand their environment, document, and make a better use of their indigenous knowledge and inform science. Overall, citizen science offers a way to gain understanding when our natural resources are out of sight. The challenge is how to further use citizen’s engagement in science to inform environmental governance and shape environmental policy. Hence, there is strong need for research to demonstrate citizen science programs for knowledge co-creation of environmental governance.

Original post, published 24/03/2022 - Alemseged Tamiru Haile, Likimyelesh Nigussie, Meron Teferi Taye (IWMI), and David W. Walker (Wageningen University)

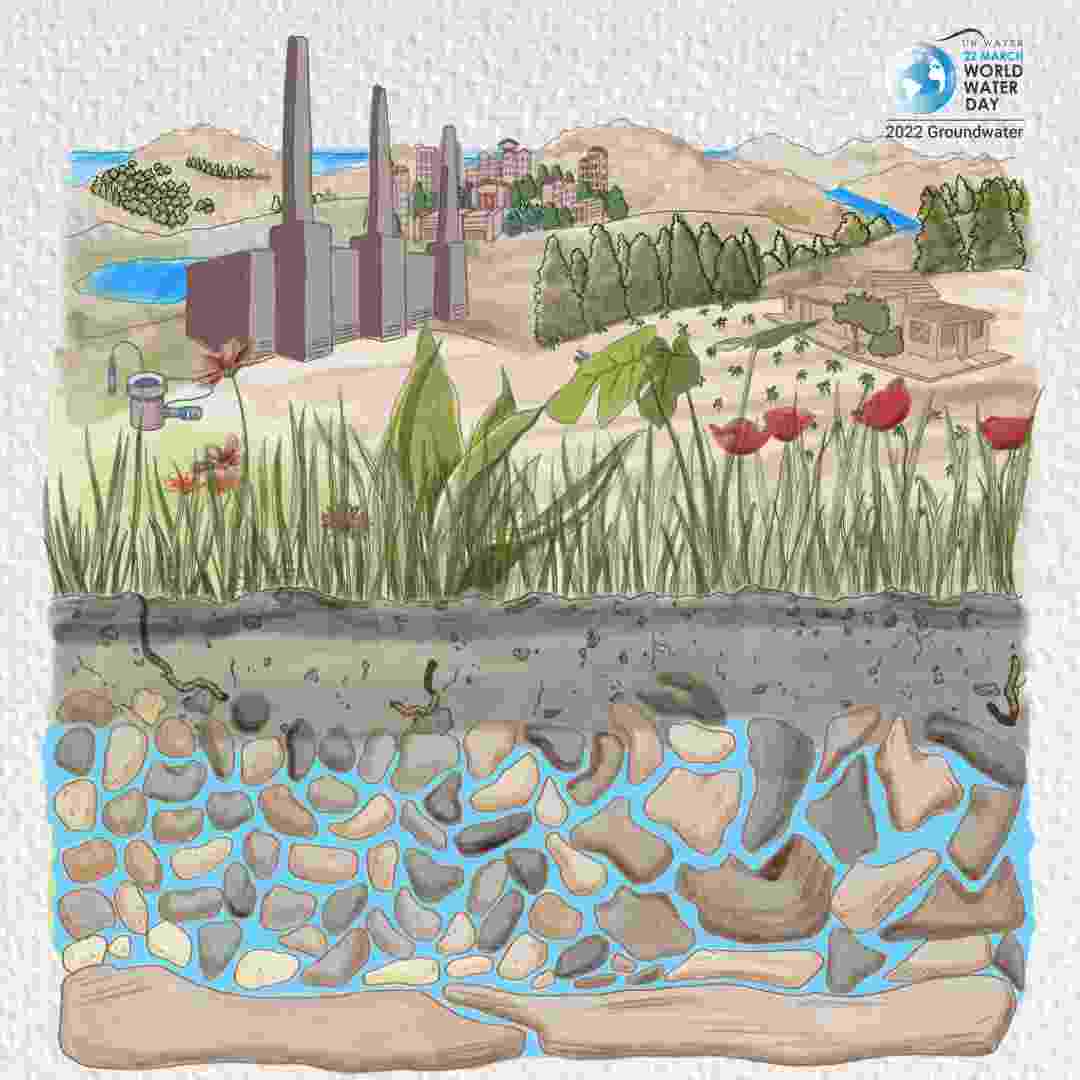

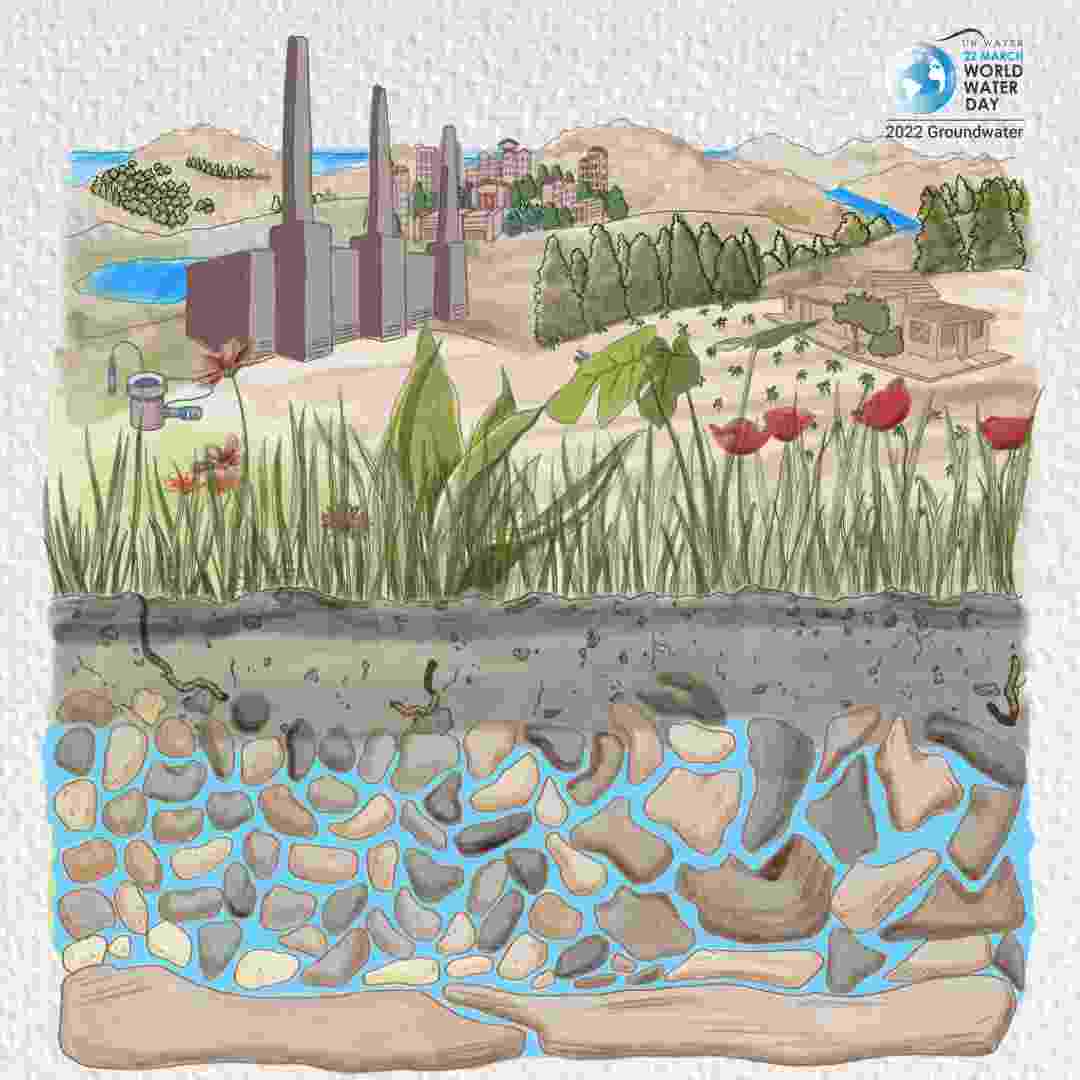

Groundwater is invisible, but it is a natural resource that is central to achieving multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) including zero hunger, clean water and sanitation, life below water, and life on land. However, in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), where surface water is either scarce or highly variable, only a tiny part of available groundwater is utilised. As a new report from WaterAid and the British Geological Survey reveals how most countries in Africa have enough groundwater reserves to face at least five years of drought, there is growing interest in unlocking groundwater potential to improve the lives and livelihoods of millions of rural farmers in SSA.

The theme for World Water Day 2022 highlights the importance of groundwater

Shallow groundwater (SGW), found below the ground surface down to around 50m, is increasingly recognised as a strategic resource to expand household irrigation. SGW allows household access to water via manually-dug wells, provides a natural buffer against drought and pollution, and improves the income and livelihood of rural farmers. Ethiopia’s National Smallholder Irrigation and Drainage Strategy (NSIDS, 2016) indicated that groundwater constitutes a substantial share of the economic potential of small-holder irrigation in the country. This strategy calls for the collection and archiving of SGW data to inform irrigation development. To support this, the Ethiopia Agricultural Transformation Agency (ATA) mapped the SGW potential for selected districts, and prepared an Atlas of SGW to guide irrigation development.

Compared to surface water monitoring, there is a huge gap in groundwater monitoring. The absence of groundwater data and information impedes sound management and governance of this critical resource. To date, existing monitoring has not provided the required data at the required time, to inform decisions on the sustainable use of groundwater. The potential consequences of this data gap are over-abstraction of SGW, pollution, and rapid depletion of the resource. However, it is never too late to start collecting data. Even in areas where SGW developments are ongoing, monitoring can inform adaptive management of SGW. Monitoring also provides baseline data for decision-making in areas where groundwater’s potential remains unexplored. Given the widespread spatial distribution of SGW, citizen scientists are ideally positioned to gather data by monitoring the wells in their own backyards.

Citizen science has multiple benefits, from enhancing community understanding of their environment to resolving data gaps for risk assessment, modelling, and better decision-making. Newcastle University (NU) and the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) have piloted a citizen science programme at the Branti watershed in the Lake Tana sub-basin of Ethiopia. A variety of methods have been employed to engage the citizen scientists, including participatory mapping to understand the SGW resource availability and variation, and direct measurement of rainfall, water level in wells, and streamflow. An expert from the district office was trained and engaged as a para-hydrologist to supervise citizen scientists, and serve as an intermediary between researchers, the district office, and the citizen scientists. With appropriate supervision, the citizen scientists demonstrated that they could collect good quality data that contributes to hydrogeological research and can inform sustainable resource management. The citizen science data were combined with traditional datasets such as laboratory analysis to assess the SGW potential for development.

Adopting a citizen science approach can fill the data gap in Ethiopia, but a lack of mandate for groundwater monitoring and resource governance is a bottleneck to institutionalising citizen science-based monitoring of SGW. The collection, archiving, and dissemination of water-related data is the mandate of the Ministry of Water and Energy of Ethiopia (MoWE) whereas the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) has vested an interest in the development of the SGW resource. MoA has no clear mandate to initiate and sustain SGW data collection but MoWE could delegate MoA to undertake monitoring in rural small watersheds for embedding citizen science-based monitoring.

Training citizen scientists on measuring shallow groundwater levels

Aside from institutional aspects, the sustainability of the citizen science programme has been threatened by other factors. Evaluation of the collected data shows that the data quality drops as the frequency of supervision declines. Citizen scientists tend to reduce observation frequency when the para-hydrologist delays visiting sites. Although communities are aware of the long-term benefits of groundwater monitoring, they need to see short-term benefits or incentives. Men, women, and youth from different social groups differ in their needs for and access to groundwater, their level of participation in management, and the amount of water they draw. While citizen science provides equal opportunities for these social groups to participate in groundwater governance, and to wider efforts in ensuring sustainability, effectively engaging different social groups necessitates understanding what incentivises them. Sustaining the citizen science programme is also challenged by a lack of ownership, as organisations with an interest in using the data are not mandated for hydrological data collection.

Training citizen scientists on measuring shallow groundwater levels in Southern Ethiopia

Alliances between researchers, organisations, and community members can create the required conditions for implementing and sustaining citizen science programmes. In literature, consensus is being established on how to ensure citizen science data quality. IWMI and NU prepared two guidelines for setting up a citizen science programme and training para-hydrologists. However, citizen scientists cannot be only data collectors - they also need to be meaningfully engaged in interpretation of the data and knowledge generation. This requires recognising and demonstrating the role of citizen science for adaptive management of the SGW resource. Further research and action are needed to show the value of citizen science data, not only in scientific research, but also in solving SGW governance problems via a community driven, bottom-up approach.