Ethnographic methods

Dr Helen Underhill

01 December 2022

View from the courtyard of the International Academy of Art Palestine, Ramallah

This methods contribution gives an overview of what is meant by ‘ethnography’ and ‘ethnographic methods’ – including immersive fieldwork, participant observation, reflexive field notes, conversations and interviews – and how these can be used to understand social worlds. I explore this using an example from my doctoral research experience of conducting long-term immersive fieldwork centred on an art school in Palestine.

Outline and application of method

Ethnography is a methodology, encompassing many constantly evolving qualitative methods, adopted by researchers in the quest to understand social contexts, socially derived meanings, and the significance of human activities. It can be broadly described as the process of paying sustained analytical attention to social phenomena through immersive relational research. Ethnographic methods include long-term immersive fieldwork, participant observation, the writing of field notes, and the recording of interactions with research participants in the form of conversations and interviews. Although these methods are diverse and deployed in different ways by each researcher, all are founded on personal observation and active participation in a given social context. Participant observation involves living alongside people and taking part in their daily lives and practices, often whilst learning a new language or set of skills.

Announcements, adverts and posters for cultural events on the street in Ramallah

An ‘ethnography’ – as an output – is often a detailed piece of writing describing a given social world or phenomenon, using existing theoretical frameworks (or developing a novel framework) to interpret and explain their significance. ‘Doing ethnography’ can involve the collection and analysis of a wide range of data considered relevant to the research questions or topic, such as photographs, objects, drawings, texts, detailed field notes, video footage, interview recordings and transcripts, census data, and archival data (and this is by no means an exhaustive list!).

Ethnographic detail, including a description of the context of activities (including time scale, location, nature of events and spaces accessible to the researcher), characterization of key participants, their activities, habits, rules and routines, is often juxtaposed with research participants’ own reflections and interpretations. Ideally, these are drawn from a range of viewpoints and reflect significant – and perhaps exceptional – social events and processes. Ethnographers often overlay or intersperse this account with their own reflections on positionality and the research process. Writing field notes can take many forms and is highly individual – from the themes, events, and aspects that a researcher considers salient, to their techniques for physically recording the information (see Flora and Andersen, 2018 on what they term the ‘kaleidoscopic’ effect of different note-taking styles colliding).

This methodology stems historically from Social Anthropology, as it was developed and codified as a set of practices in the early 20th century by anthropologists such as Malinowski, for the study of remote and bounded communities (see Kuper, 2018 for a primer in the history of the discipline, including its roots in the maintenance of imperial power, and further exploration of Malinowski’s methodological innovation and its relationship to Functionalist theory). Ethnographic methods have since been adopted and adapted by disciplines such as Sociology, and the Humanities and Arts more broadly. The racialized and colonialist roots of Anthropology have also been subject to ongoing critique, through which greater reflexivity and attention to researcher positionality and power flows has been encouraged.

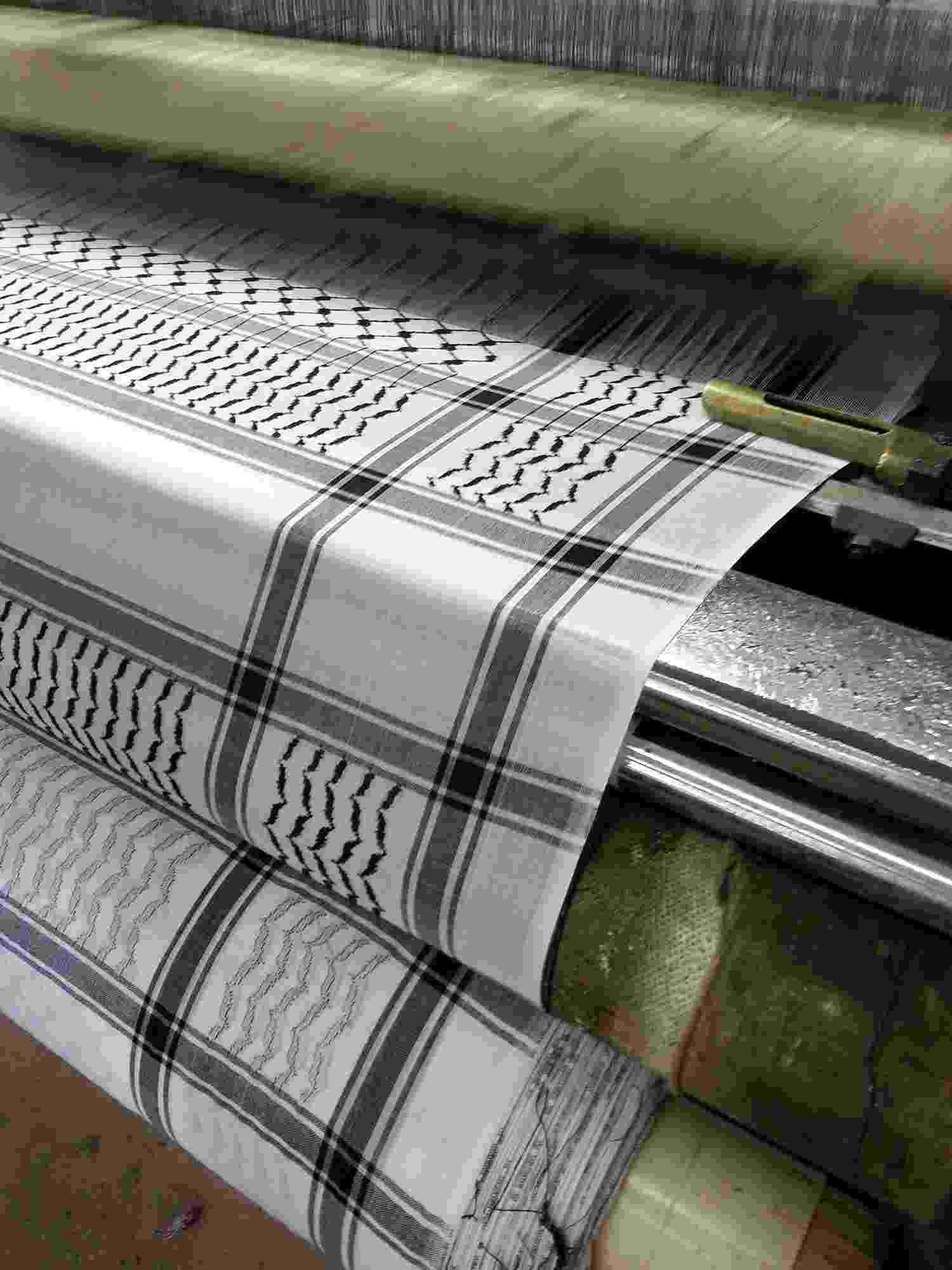

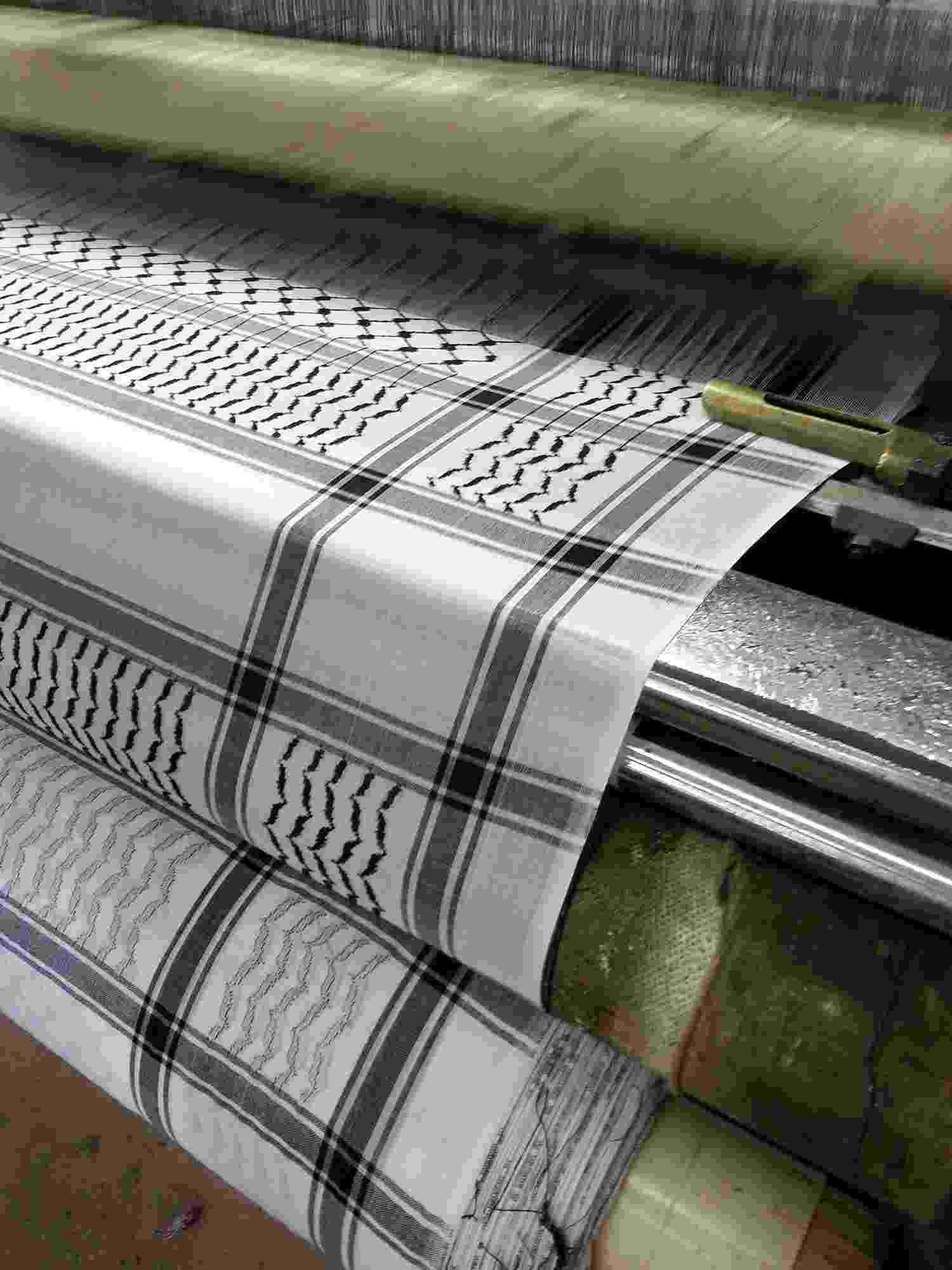

A factory in Hebron creating traditional ‘Keffiyeh’ scarves – symbolic of Palestinian political, social and cultural identity and resistance.

Key features of Ethnographic Methods:

- Prolonged research and long-term or open-ended engagement (researchers are often engaged with their field site or community over years or decades). Although there is no set threshold, researchers can cumulatively spend hundreds – or thousands – of hours engaged in various fieldwork activities (see Ingold, 2014 for a critique of the overuse of the term ‘ethnography’, and how to reclaim the meaning of the word, and reassert the value of Anthropology as a discipline).

- Immersive fieldwork (researcher aims to become culturally ‘embedded’ with community, to gain – as far as possible – an ‘insider’ understanding of social phenomena, and how social relations are shaped within their context).

- Observational (researcher watches, listens, notices, and aims to move closer to understanding).

- Experiential (researcher becomes involved in daily activities).

- Engaged, relational and reflexive – the researcher dynamically reflects on their own positionality and experience, shortcomings, concerns, emotions, and responses within the cultural context being studied, as well as the wider socio-political and power structures within which they work (see Shah, 2017 for extended discussion of this).

Within interdisciplinary research, ethnographic methods are particularly valuable as they can offer a holistic overview of complex social, political, and cultural processes. In addition, they can be used to reflect on research cultures themselves, moving across disciplinary boundaries, and drawing together different worlds, and different types of data.

Introduction to ethnographic methods

In this video, I introduce varied aspects of the Ethnographic Method through the example of my doctoral research experience of long-term immersive fieldwork centred on an art school in Ramallah, Palestine.

Differentiating this method from adjacent/similar methods

The following data collection techniques can be used as elements of ‘doing ethnography’, but do not constitute ethnographic engagement in isolation:

Household Surveys and Questionnaires are more fixed in focus, gathered at a single point in time, place less emphasis on context, may lack nuance, and do not engage in reflection on the research interaction and data-gathering process.

Qualitative Interviews: It is possible to conduct structured or semi-structured Qualitative interviews without ‘doing ethnography’, as the definition of the latter rests on sustained, immersive engagement by the researcher.

Participatory Research is designed and conducted with the group or community in question and differs from the similar-sounding Participant Observation in significant ways.

Mobile Methods or “Go-Alongs” involve moving through the research environment in the company of a research participant and recording their response to relevant features of the landscape, actions, or events.

Adjacent methods could include:

Narrative Research - the analysis of a range of texts, which could include stories, journals, conversations, letters and life histories, to understand how people construct meaning through narrative. NB. Some of these distinctions are quite arbitrary, and attempting to draw clear boundaries can result in circular arguments, for instance, field notes or interview text could be considered as types of narrative research data, whether or not they were collected as part of a wider ethnographic project.

Grounded Theory - developed within the Social Sciences, in answer to academic anxieties about whether qualitative methods were sufficiently analytically rigorous. Grounded Theory is an inductive method in which a hypothesis generated from qualitative data is repeatedly tested and accepted or rejected. It aims to provide a codified process for approaching qualitative research data (for instance, through iteratively coding textual research data).

Case Study Research – the collection of single case studies to support, illustrate or triangulate research claims. More tightly bounded and less expansively engaged in wider cultural and social factors than ethnographic research.

The Dome of the Rock, Temple Mount, Jerusalem - a location of huge significance to Palestinians.

Women meet outside the Dome of the Rock, Temple Mount, Jerusalem.

Why use this method? What areas of research is it appropriate for?

Key strengths of ethnographic methods:

- Capturing richness of detail (‘Thick description’ for understanding nuance, specificity, complexity, and contradiction).

- Reflexive potential – to reflection on one’s own position as a researcher and evaluate the impact of one’s research.

- Differentiating between what people say and what people do in different situations. Examining instances when these differ, and asking questions about why this might be, can offer fresh insights into complex issues.

- Allows research to proceed from a foundation of respect for the complexity of human experience, acknowledging the partiality of all accounts and the situatedness of researcher – in time, space, race, class, and power structures.

- Offers the opportunity to include diverse voices and perspectives.

- Helps us to move between observing particularities and drawing broader theoretical insights that are useful for problem solving. Ethnography is a theoretical practice, in which the researcher abstracts from the qualitative detail of lived experiences in order to analyse ways of thinking and acting.

- Holds the potential for incorporating and addressing contradictions.

An illustration of the complexity and contradiction that ethnographic research attempts to untangle – t-shirts for sale in the Old City of Jerusalem with extremely conflicting political and cultural messages

Ethnographic methods are appropriate for research that requires depth of understanding and cultural sensitivity. For instance, to understand how diverse social actors in a specific context are likely to react to an intervention such as the building of a dam, or the privatization of water provision, and how this links to specific local histories, politics, and dynamics.

These methods are particularly appropriate for investigating questions of how human beings live in the world, including:

- Ritual, symbolism, and people’s beliefs or religious practices

- Health and bodily practices

- Exchange, production, and economic practices

- Life events such as births, deaths, marriages, and how these are negotiated, marked and understood

- People’s relationship to their environment

- The negotiation of power structures

Case study

In this video, I describe a hybrid participant observation/drawing workshop method that developed within my research, through teaching life drawing classes with art students in Palestine. Ethnographic detail captured through this research process included descriptions of the classes, drawings and photographs, individual responses from students, and my own reflections on my role as a teacher, and as a researcher.

Practicalities and ethical considerations

In this video, I address some practical aspects of ethnographic research such as gaining access, working through gatekeepers (key figures whose approval is vital for establishing access to certain social groups and research contexts), and building rapport.

I also briefly explore some of the physical, emotional, and psychological challenges of long-term fieldwork (see Pollard, 2009 for an honest discussion of difficulty and emotion within ethnographic field work), as well as ethical concerns such as the security of interlocutors, consent, and the dynamic between overt and covert aspects of research.

The process of teaching an art class in this environment helped me to learn about the way the institution operated, and the way in which students responded to this. This informed my eventual ethnography, acting as the empirical foundation for my subsequent theorisation of how individuals approach, adapt and subvert the demands of such an institution for their own purposes.

Who could be involved – research participants, communities?

Defining the community within which an ethnographic study will be based can be complicated, as individuals’ membership in multiple groups is common, and some groups may be more (or less!) accessible to the researcher than others. Choosing a ‘boundary’ for one’s research project is thus highly dependent on the nature of the research questions you are addressing. This definition often involves consulting local, situated understandings of where a community begins and ends, and who is incorporated in, excluded from, or peripheral to the group.

An ethnographic research project could be bounded by work with:

- Communities of location, such as a rural community, village, mountainside or river basin, or an urban community or neighbourhood.

- Communities of practice or occupation, such as water utility company workers (perhaps an organizational ethnography), a school or university class or year group, groups such as fishers, boat dwellers or poultry farmers, or members of a club or organization such as a canoe club.

Research could also be centred on demographic subgroups or intersectional layers and markers of identity (for instance women, religious groups, LGBTQIA+, minority community groups).

A mosaic memorial to martyrs of the Palestinian cause - Ramallah. This includes visual signifiers such as the Sabra cactus, women and children holding pictures of martyred young men, olive trees and a dove.

A detail from the Ramallah Martyrs Memorial in which a woman in traditional Palestinian dress shelters a child and cradles a basket of rocks, symbolic of resistance to the military might of Israel.

Critiques of this method

There is a vast critical literature on the origins of the ethnographic method in Anthropology, a discipline that was historically deployed as a colonial tool of domination (please see the links below for some suggested readings). Classical ethnography – in the sense of researching and writing about a group - has been justifiably critiqued as a racialized process of othering (Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s seminal book Decolonizing Methodologies offers a thorough critique of colonization and othering-through-research) . Questions and ambiguities regarding research as a potentially ‘othering’ process remain central to research that attempts to understand the lives, values and practices of other groups or communities through mutual engagement.

Ethnographic practice has been repurposed for activist aims, as a tool for theorization by formerly marginalized groups, and the boundaries between researcher and researched have been productively rethought by ‘insider’ anthropologists. Despite this diversification, Decolonization of knowledge production, hierarchies and institutions remains an ongoing process within the various disciplines that make claims to practicing ethnographic methods.

A detail from a door, Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem. Ethnographic methods can help record material detail, associated cultural practices, and their wider politics.

Summary of information

Ethnographic methods are centred on personal observation and active participation by a researcher in a given social context. These methods include immersive fieldwork, participant observation, reflexive field notes, conversations and interviews used to explore people’s values, concepts, and material practices. They are well suited to long-term, socially and culturally engaged reflection on complex and contested issues and can – done well – allow researchers to reflect on their own positionality and power relations, which are crucial to addressing Global Challenges.

Reflections:

- How might ethnographic methods be useful to my research?

- What difficulties might I encounter in using these methods within my research context? For instance, think about access, ethics, security, and participant consent.

-

What would I really like to understand about (my specific research context/issue), and how would I go about finding this out using participant observation? What groups would I approach, and what activities could I undertake with people?