World Cities Day: Better city, Better life

COVID-19, water infrastructure, and building resilience in Delhi Urban Agglomeration, India

31 October 2021

Urban areas, with a high concentration of population and economic activities, have been the epicentre of the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 has “revealed the limitations and challenges of our urban environments” (UN Habitat), and made it clear that the health and economic impacts of COVID are intrinsically linked to both climate change and inequality. UN Secretary General António Guterres said “COVID-19 recovery and our planet’s repair can be two sides of the same coin” - we have an opportunity to focus the post-pandemic recovery on transforming cities to become more equitable, healthy, environmentally friendly, and resilient.

Our cities are currently not built to deal with impacts of multiple risks and hazards, like high intensity floods resulting from climate change, or a lack of infrastructure leaving citizens unable to access clean water. The World Cities Day theme of ‘Better city, Better life’ encompasses the need for action not just on climate change adaptation, but on issues like urban poverty and ensuring access to basic services for all. A multi-layered approach across multiple sectors is needed in our urban planning and development to ensure global resilience.

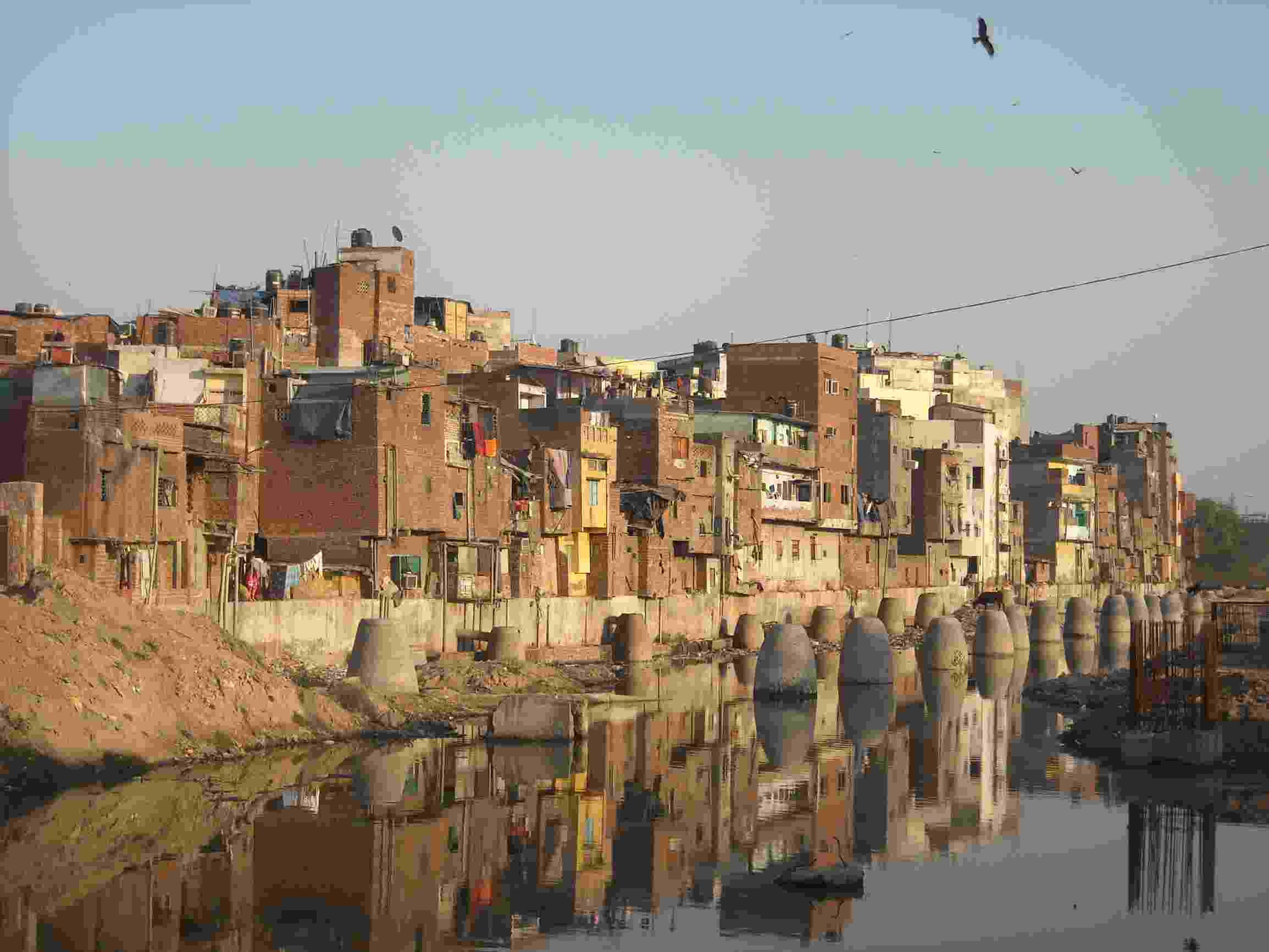

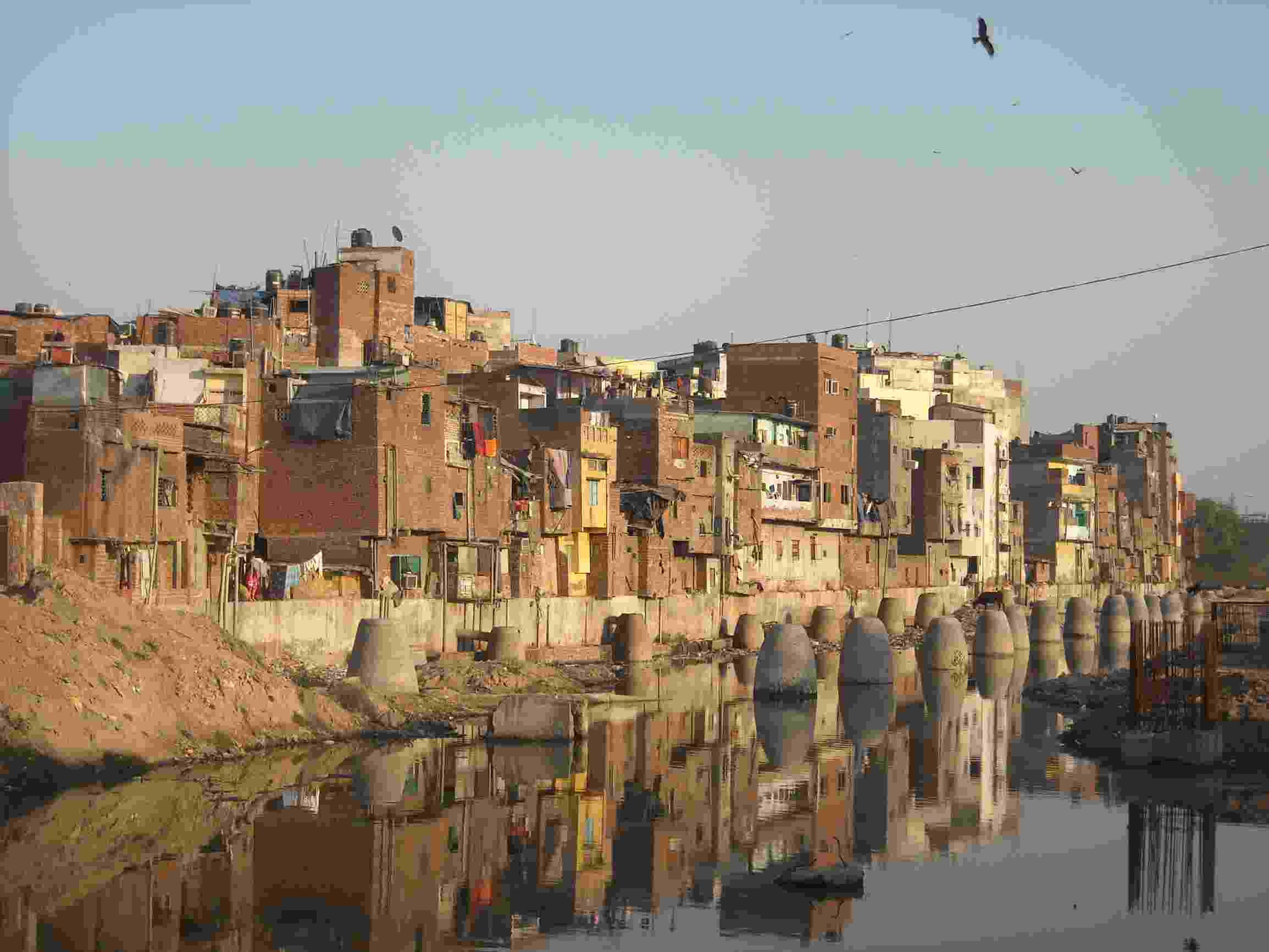

Dubbed the ‘Inequality Virus’ by OXFAM, COVID-19 has exposed deep inequalities in society across the globe, particularly in water access, with the most vulnerable communities suffering the greatest impact. There are more than 880 million people living in informal settlements around the world; these communities face heightened vulnerability to impacts of climate change and other risks due to three key factors: they are often built on fragile sites exposed to high risks; the socio-economic characteristics of residents - such as high levels of poverty and illiteracy - mean the communities have low capacity and resilience to withstand impacts; and the political and institutional marginalisation of these communities, for example the absence of basic services or non-recognition of informal settlements, often results in a lack of meaningful investments in risk-reducing services and infrastructure. Climate change and COVID-19 are deepening urban poverty - an inclusive approach to planning, building, and managing cities for climate action and pandemic recovery is needed.

Informal settlement in Delhi - Sistak, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Water and sanitation took central place in policy circles and day-to-day conversations during the first waves of the global pandemic. Personal and household hygiene are hugely important in limiting the spread of disease, and WHO advice to citizens was to practice regular handwashing and to maintain appropriate physical distance from others. For many of Delhi’s citizens living in unauthorised colonies, following the WHO advice was just not possible. An estimated half of the city’s residents (16.7 million in the 2011 Census) are not connected to the centralised water network, relying on other means such as tankers, private taps, tube wells, and public standpoints. Shortages of water are common in many areas of the city, and some poorer communities receive water for just a few hours each day.

Water tankers provide drinking water at the makeshift Yamuna flood relief camp

The poor planning and construction of this inadequate housing also leaves these communities vulnerable to climate change impacts like flooding, and the ever-increasing conversion of natural areas into urbanised zones puts additional pressure on existing infrastructure. Redevelopment policies - in some cases little more than eviction and displacement policies - displace thousands of citizens each year. Part of our India Collaboratory’s work involves using household surveys to capture the lived realities of water-related risk in unauthorised colonies and a socio-economic analysis to establish a common understanding of the circular economy and resilience in the urban water sector. They are also contributing to multi-stakeholder water-sensitive planning policies to improve water infrastructure and management, and nature-based solutions to build resilience and capacity for climate-induced hazards like flooding.

The devastating impact of COVID-19 highlighted just how important water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) is to public health. WASH, urban infrastructure, and climate vulnerability are inextricably intertwined and should be a fundamental part of funding and planning for the future resilience of our cities. By failing to address water insecurity of our most vulnerable, we jeopardise public health, economic activity, supply chains, environmental protection, and social stability. The global post-pandemic recovery provides an opportunity to rethink urban planning and management to make structural changes and institutional reforms that protect the most vulnerable and create a resilient and inclusive urban future for all.